Around the World on a Bicycle

Berkhamsted-born Thomas Stevens had great ambitions – which led to a pioneering trip on a Penny Farthing, and a search for an African explorer.

How much did you pack for your last holiday or weekend away? We bet it was more than Berkhamsted-born Thomas Stevens, who took only a clean pair of socks, a spare shirt, a mackintosh (which acted as a bedroom and tent) and a 38 Smith and Wesson as he began the American leg of his round the world trip.

How much did you pack for your last holiday or weekend away? We bet it was more than Berkhamsted-born Thomas Stevens, who took only a clean pair of socks, a spare shirt, a mackintosh (which acted as a bedroom and tent) and a 38 Smith and Wesson as he began the American leg of his round the world trip.

Thomas was born in Castle Street in Berkhamsted. His parents were Ann and William, who was a labourer. William emigrated to Missouri in the US, returning when his wife became ill. Later, in 1871, when Thomas was just 17 the whole family moved out to the States.

Thomas Pauly of the University of Delaware wrote the introduction to a reissue of the cyclist’s book – Around the World on a Bicycle – and in an interview said: ‘His working man life was going nowhere – he was a worker/labourer – he worked on iron mills, and in mines – he was ambitious and worked his way up. But he was going nowhere. He read accounts of people who had tried and failed to ride around the world and he decided to give it a go. He didn’t even know how to ride a bike – he went to San Francisco, bought the bike (a black-enamelled Columbia 50-inch ‘Standard’ Penny Farthing with nickel-plated wheels, built by the Pope Manufacturing Company of Chicago) and rode it around. Then off he set from the Golden Gate bridge!’

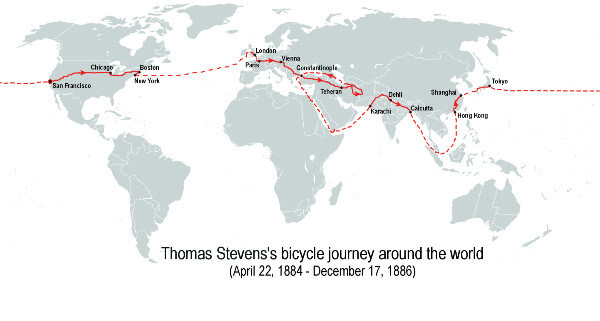

His first trip was across America – it took him just over 103 days to cross from San Francisco to Boston (including 20 non travelling days due to weather). That was 3,700 miles of travelling along rough wagon trails, railroad ways, canal towpaths and irregular public roads. On a Penny Farthing! When he went over the Sierra mountains he only had rough wagon roads to follow. He found the best way was to walk his bike on the railway tracks. But with no timetable, he was at the mercy of the trains – and at one point had to hold the bike over a precipice as the train passed.

This trip caught the attention of Outing Magazine in New York, and they appointed Thomas as special correspondent, and he headed to Liverpool to begin his epic journey across the rest of the world.

After making his travel arrangements, Thomas set off from Edge Hill Church on 4 May 1884, where several hundred people watched his departure. His route through England took him through his hometown of Berkhamsted, before he caught the Newhaven ferry to Dieppe, France.

He must have been an unusual sight on his bicycle, a white pith helmet (which earned him the nickname General Gordon) atop his head. His journey through Europe was relatively uneventful but it was when he headed out of Teheran (where he had stayed with a Shah) that things got tricky.

The Afghanistan border was guarded fiercely and he was arrested. However, he entertained his guards with a demonstration of his bicycle’s speed as they took him to a villa where he was detained. Here he said he was well fed, and was given soap, new boots and even biscuits imported from England.

Once released, he was escorted to Persia, but the guards, nervous of his speed on the cycle, disassembled it and it was carried by a packhorse, which unfortunately laid on the large wheel, causing some severe damage. Fixed by Afghan gunsmiths, the bike and Thomas continued on his journey.

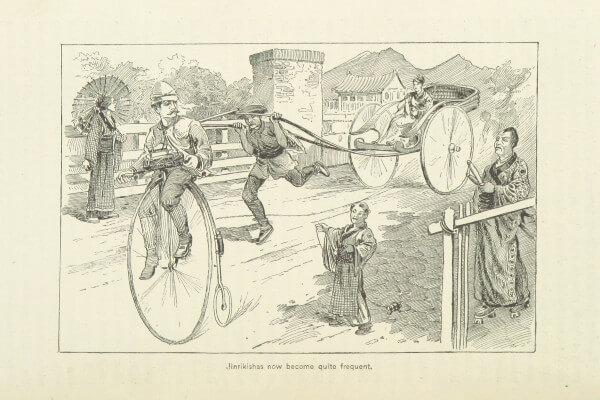

As he travelled further East, Thomas Pauly says that the adventurous cyclist caused quite a stir: ‘people were seeing a white man for the first time, on a shiny metal contraption. They were astounded and they thought he was a deity.’

In China the welcome wasn’t quite so warm – they chased after him and tried to stone him – a Chinese official protected him from rioters who were angry over a war with the French (presumably the difference between an Englishman and a French man was not apparent to them).

His cycle trip ended on 17 December 1886, at Yokohama, Japan, when he had cycled around 13,500 miles.

But that was not the end of his adventures. In 1888 The New York World asked Thomas to join its search in East Africa for the explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who had travelled up the Congo but not been heard from for 18 months.

Thomas set off on a six-month trip, which saw him hunting big game and climbing Kilimanjaro – as well as finding Stanley’s camp.

In his memoir, Scouting for Stanley in East Africa, he wrote: ‘I had not ‘found Stanley,’ as Stanley had found Livingstone in 1871; the circumstances were altogether different. I had, however, gratified a pardonable journalistic ambition in being the first correspondent to reach him and to give him news of the world, after his long period of African darkness. That I had done this under most trying conditions, Mr Stanley fully appreciated; and warmly reciprocated by showing me every courtesy in his power, on the march to the coast, in Zanzibar, and in Egypt.’

Thomas returned to England around 1895, got married and became manager of the Garrick Theatre in London. He died in 1935 and was buried at St Marylebone Cemetery in East Finchley, London.

Thomas returned to England around 1895, got married and became manager of the Garrick Theatre in London. He died in 1935 and was buried at St Marylebone Cemetery in East Finchley, London.

We bet you’d love to see that famous bike wouldn’t you? Unfortunately, while cycle manufacturer The Pope Company preserved Stevens’ bike for 50-plus years, it was lost to a scrap metal drive during the Second World War…