Making it in the Movies

Ever wondered why the National Film Archive ended up in a Hertfordshire market town? We take a look at its story – and what happens there now…

The BFI National Archive is one of the largest film archives in the world. Its history goes back to 1935. At its inception, it was known as the National Film Library, and had a tiny budget and a staff of only two. It became the National Film Archive in 1955, and, in 1992, to reflect the growing amount of television-related material being archived, the National Film and Television Archive. It finally took on the moniker of BFI National Archive in 2006.

When the collection began, it was housed at the BFI’s London headquarters, but it became clear that, as it grew, it would need new, dedicated storage space. Films, of course, must be kept away from moisture, heat and strong light if they are to be preserved.

So in 1940, a state-of-the-art space was opened in Aston Clinton. In 1968, the archive moved once more, this time to new premises, which became the home for acetate films.

Ten years later, a new site in Warwickshire was established to house nitrate films.

However, according to Robin Baker, head curator at the BFI National Archive, a ‘truly transformative moment for BFI’ happened when John Paul Getty Junior donated cash to the organisation.

His generous donation led to the opening, in 1987, of the new, purpose-built J. Paul Getty Jr. Conservation Centre on a 9-acre site in Berkhamsted. This cash injection also allowed the BFI to move to new headquarters in Stephen Street, central London.

While the Warwickshire site keeps safe many rare films that are considered highly precious – especially film negatives and highly unstable nitrate film – the Berkhamsted site houses rare films stills, costume and production designs, a huge of collection of films that are still shown in cinemas and much more.

The archive is the ‘busiest in the world,’ says Robin, and is the holding place for film stills, 35mm film, and a tape collection along with many associated items related to British filmmaking – so there’s scripts, business papers and correspondence.

Among the cardboard filing boxes is a real treasure for Star Wars fans – the continuity supervisor’s shooting script for something called ‘The Adventures of Luke Starkiller’ by George Lucas. Continuity polaroids, which offer candid photos of the cast/crew on set, and scribbled annotations make this something very special for film geeks.

You’ll find scripts and correspondence from films by Alfred Hitchcock, Derek Jarman and David Lean, along with 1.5 million film stills and 20,000 film posters.

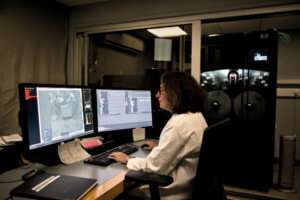

It is also the location for restoration work. Robin says: ‘It’s been a great location for us and a great local employer. [There are between 80 and 100 colleagues working at the conservation centre.] Many of the people who work for us come straight from school. They learn some very rare skills and of course once they learn those skills, many of them stay with us for a long time.’

And it’s hardly surprising – some of the work must be a film enthusiasts’ dream. ‘They might be working on the original negatives that went through Alfred Hitchcock’s camera. How exciting is that?’ says Robin.

The skilled staff work on restoring films. For instance The Epic of Everest, a 1924 documentary about the Mallory and Irvine Mount Everest expedition, once restored, was chosen to be shown at the We Are One: A Global Film Festival, an international online film festival organised during the pandemic. Not everything is so old though – Monty Python legend Terry Gilliam sat in on the restoration work of his 1977 film Jabberwocky, to ensure the 2017 version matched his Seventies ideal.

The skilled staff work on restoring films. For instance The Epic of Everest, a 1924 documentary about the Mallory and Irvine Mount Everest expedition, once restored, was chosen to be shown at the We Are One: A Global Film Festival, an international online film festival organised during the pandemic. Not everything is so old though – Monty Python legend Terry Gilliam sat in on the restoration work of his 1977 film Jabberwocky, to ensure the 2017 version matched his Seventies ideal.

One of the major projects for the archive is transferring video tape into a digital format, explains Robin. ‘In the future there won’t be any machines left to play video on, so there’s a real urgency for this work.’ The archive has ‘world-beating facilities for digitisation’, allowing the material to be preserved for future generations.

The largest part of the national collection is TV. Although the BBC takes care of its own content, the archive preserves the output of ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5.

Of course an archive is never complete. Gems still pop up from the past. The archive has a list of coveted films, believed to be lost. On this list was a 1923 movie entitled Love, Life and Laughter, starring Betty Balfour, known as the ‘British Mary Pickford’. However, the Eye Filmmuseum in the Netherlands actually found it had a copy, which has since been acquired and restored by the BFI. The BFI National Archive also found a tiny film fragment, shot in Technicolor, of another iconic 1920s star – Louise Brookes – from her lost film, American Venus (1926).

We gave Robin the hard task of picking out just a few of the most interesting pieces that are stored in the archive. He chose an invitation to Peter Sellers’ first birthday party, production designs from David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, and Cecil Beaton’s Academy Award for My Fair Lady.

He also describes a letter from US Director William Wyler, explaining how he had seen footage of an unknown actress and was going to cast her in the lead in his next film. The film? Roman Holiday. The actress? Audrey Hepburn.

Visit the BFI National Archive

The archive is usually open (pandemics aside) once a year, to allow the public to get a glimpse of what happens behind its doors, and what the collection includes. Robin says it’s amazing how complex the processes are, and how they mix the analogue world with the latest extraordinary technology. Amazing work going on right on our doorstep!

This year’s open day is on 12 September, though booking may have closed by the time you see this. See www.heritageopendays.org.uk for details.